John Williams' score is, of course, one of the great works of the 20th century. I don't think it is hyperbolic to say that without it the film might easily have been a campy cult classic, known but not legendary. Each theme is perfectly evocative, and perhaps none so much as The Imperial March. The piece just feels dark, haunting and mysterious.

What makes it sound that way? I believe that the difference between good and great in this piece was one note choice. On the first pass it might sound as though the harmony goes between the i and the VI chord. If you asked a musician to play it from memory, they might do something like this:

|

| These aren't the chords you're looking for. |

It is interesting to note that it is possible the minor VI chord may not be a real departure from the key. The minor third of the VI chord exists in the harmonic minor scale (kind of), so the music may actually have been written from more of a melodic, rather than a chordal perspective. (I'd expect the prior from Stephen Sondheim, the latter from, say, Randy Newman) If Williams wrote an F#, it would suggest that he was thinking of the melody and harmony as based in G harmonic minor. Gb would suggest that he thought of the song temporarily going to an Eb minor chord. For answers, we turn to the original score. "my only hope!"

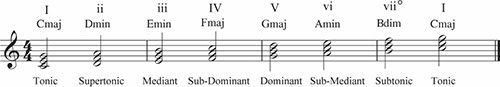

Aha! Note the F# in the violas. It would seem that the piece is based in the harmonic minor scale. There is, of course, no such thing as a harmonic minor key that I know of. That is, I've never seen a key signature with both flats and sharps. In World Music there are many scales and modes that contain both, but it gets hairy fast. Most (Western) music is written in diatonic keys, including many that sound atonal or deviate heavily from the key. Harmonic theory is taught to beginning students like so:

It is relevant to The Imperial March to point out that the VI chord is still major. A minor VI chord in the key of G "harmonic" minor would be spelled Eb, F#, Bb. Because the Eb and F# are a second apart (albeit an augmented second) I would technically call this an Eb2 chord, even though it sounds like Eb minor. And that, kids, is why we avoid mixing sharps and flats.

Williams throws a curveball only a few measures later, however:

The brass, playing the melody, have a Gb. What? It gets worse. In that one measure, the strings no longer play F#, but switch to Gb. "It's a trap!"

|

| This kind of thing makes violinists go crazy. |

I believe the most likely reason for this change is that John Williams, like all good composers and conductors, wants his music to be read and performed as easily as possible. There is no theoretically correct way to write this, so he chose the way that made it easiest to read. In the first example, he used F# because it was easier than making the Violas jump back and forth between G and Gb. They would be used to seeing F# in G minor. When the trombones have a Gb, it is because an F# would make it look like they are using the fourth (Bb to F#) but it sounds like a third. "Your eyes can deceive you, don't trust them." It is a bit confusing and jarring to play, and no one wants that. A happy orchestra is a good orchestra.

The last example, where it changes from F# to Gb over the bar line happens for two reasons. 1) He wanted the chord to be consistent across parts in that measure so the conductor could look at the page and not see an enharmonic mess, and 2) who cares what the violins think? This is a case where pragmatism trumps theoretical purity.

Delving into the theory behind this piece my vain attempt to explain why it is so deeply and indelibly impactful for so many people. Undoubtedly the music is enhanced by the visuals on screen, but the reverse is also true. The music paints the character, masterfully in this case. Musicians make tiny compositional decisions all the time, and often a little choice can completely alter the tone. Williams' choice of Gb (or F#) makes all the difference in this one.

I think one of the big motivating factors here is avoiding V. And not just avoiding V, but 1) reharmonizing the F sharp in a way that is quite unnerving and 2) extending that to the leading tone of V (C sharp). Both of these create minor triads, yes, but it also makes a "things are a half step away" type of sound, which Radiohead is very fond of, as is Danny Elfman but in a very different way.

ReplyDeleteI also like hearing that E flat chord as a "surrogate V," or as an appoggiatura that got stuck: the Eb and Bb don't have the chance the resolve down.

Let's not forget that the primary motif is an Eb major triad. And all of the roots are whole steps apart...but the chords are minor, making it decidedly un-wholetoney.

Sorry. I knew once I started it would hard to stop!

God, I needed you on this post! I like the appoggiatura idea, because that's kind of how it feels. And yes, it's hard to stop analyzing this one. I didn't even delve into the next part, where it abruptly moves to C# minor.

Delete